Research Highlights

The role of the architect is changing, in relation to wider changes in the construction industry and models of procurement.

The role of the architect is changing, in relation to wider changes in the construction industry and models of procurement.

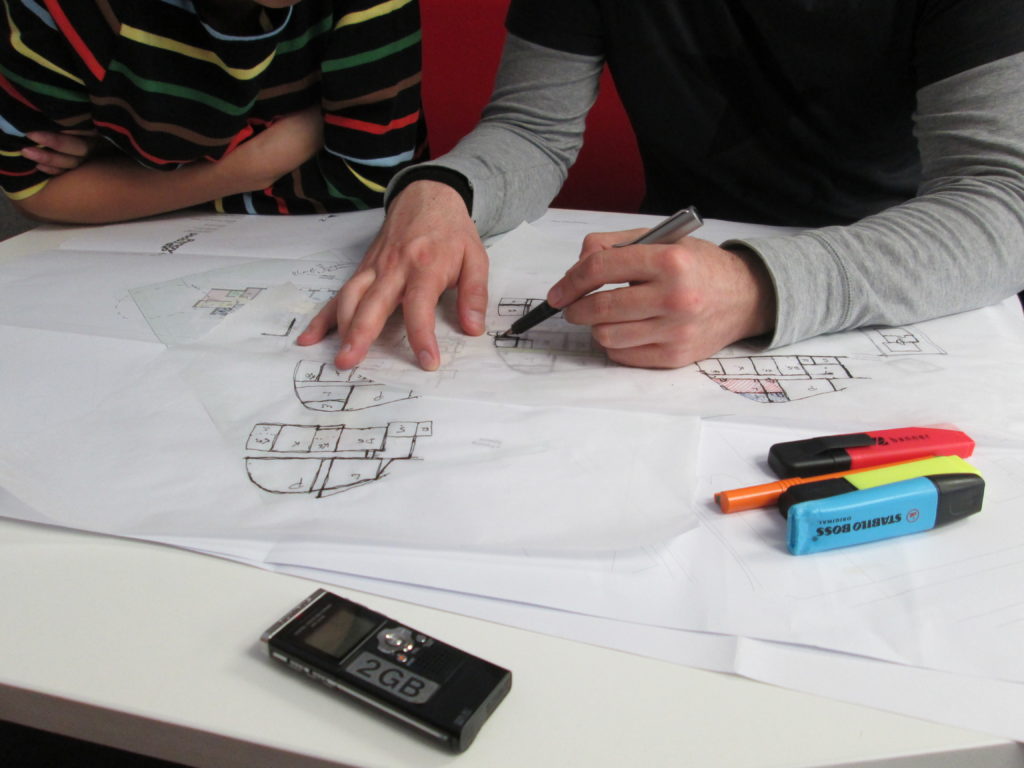

- These changes call for collaborative ways of working, yet architectural education can encourage a separation between architecture and building, design and construction. This has implications for the image of architects and working relationships between professions.

- Care providers, developers and contractors still recognise the significance of architects’ role, for instance, in co-ordinating complex technical information, translating specialist knowledge, design and spatial thinking, problem solving and adding value. Good communication skills are also seen as vital to the role.

- Creating better spaces for dementia and later life care is not just about the product but about the processes of design and construction. Methods of commissioning, procurement and ways of working together have important implications for the finished building, and the experiences of building users.

- Models of commissioning and procurement can impact on designs, for instance, on Design and Build contracts, the designing architect is not always retained, and their expertise in design for dementia or later life may be lost. The competitive tendering process can be a barrier to consulting with building users early on and to collaborative ways of working.

- There is extensive guidance available for age friendly and dementia friendly design, but it can conflict with financial constraints and regulatory requirements. For instance, although gardens are recognised as important for well-being, they are affected by processes of cost cutting.

- Principles for dementia and age friendly design need to be specified clearly in the brief and tender documentation, to prevent key design features being lost e.g. because of cost considerations and ‘value engineering’ exercises.

- In guidance on age/dementia friendly design, the focus is generally on design for older residents. Staff as building users tend to be overlooked, and staff spaces such as staff rooms, laundries and kitchens have received less consideration in design guidance.

- There can be a disconnect between design intentions and the operation of a building. For instance, there is a tension in designing accessible outdoor spaces which are then kept locked due to concerns about resident safety.

- Consultation with building users (staff, residents, relatives) generally does not happen on projects, unless the client allocates adequate time and resources for this. Consultation can be left too late in the process, limiting potential for users to shape the design.

- These issues are situated within wider constraints on funding for health and social care, which can limit resources for consultation with building users and the take-up of principles for good design, as well as shaping the choice of particular procurement models.

- There is a need for more guidance and training for architects and other design and construction professionals on why, when and how to consult with building users. An awareness of designing for diverse building users, including people living with dementia, should be incorporated into architectural education.

- For dementia and age friendly design to happen this requires a collaborative effort across the different construction trades and professions, planners, regulators, commissioners and building users (including older people, people living with dementia, staff, and relatives). A shared sense of the vision and values of a project across the design and construction team should be embedded in the brief and developed through ongoing working relationships and practices.